Not all pastors value camp.

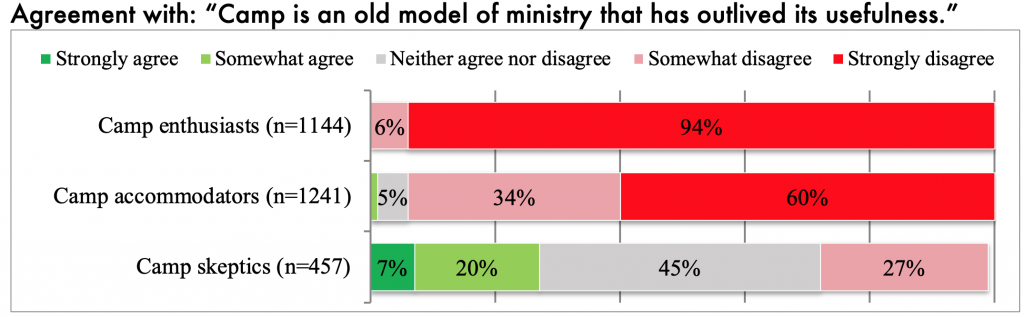

Some are benignly dismissive, while others are almost hostile. We collectively call this group the camp skeptics. In our recent survey of ELCA pastors and deacons, just under one in five (18%) were categorized as skeptics. These folks do not give to camping ministries, never (or hardly ever) visit, and are generally skeptical of camp’s contributions to ministry. Almost half (42%) of skeptics do not know enough about their local camp to render an opinion about the director or the ministry, and over half of those that have an opinion would be fine if the camp closed. Almost three-quarters (72%) agree or demur (neither agree nor disagree) with the statement, “Camp is an old model of ministry that has outlived its usefulness.” Notice that for most of the camp skeptics, it is not just an aversion to a specific camp. They are skeptical of the camp model itself.

My occasional encounter with camp skeptics was one of the main reasons I left my camp job in pursuit of camp research nearly a decade ago. I distinctly remember one pastor’s observation of the local camp director’s appeal for support, “It felt like he was asking for money to save the dinosaurs.” For me, the power of camp has always been obvious because I experienced it first-hand and witnessed its transformative power in the lives of others. But my story is not everyone’s story. It is true that the call to ministry often leads through camp. Half of our ELCA survey respondents agreed that their personal camp experiences were instrumental in their call to rostered ministry. Most of these pastors and deacons are camp enthusiasts or camp accommodators (see previous posts).

Respondents to the 2020 ELCA Rostered Minister Survey.

But not all roads to ministry wind through camp. Even among clergy in the ELCA, where camp experiences are very common, more than a quarter (28%) neither attended camp as a child nor worked on summer staff. Lack of personal experience does not mean they will become camp skeptics, as we noted when discussing camp enthusiasts, but they are more than twice as likely to be skeptical.

Another important consideration is that not everyone has an amazing, life-altering experience at camp. Life-change happens with remarkable frequency, but most participants have positive experiences with more subtle impacts. A small portion of participants (usually around 3% in our surveys) do not enjoy camp, and some have overtly negative experiences that leave lasting impressions.

Where Skeptics Come From

Here we come to the primary fear of camp skeptics: that camp may be harmful.

Denominational camps are sanctioned church activities that make big promises. If a congregational leader promotes a camp experience that turns out to have negative consequences (even for a single person), they will be much more hesitant to encourage participation in the future. What if the camp promises life-change and delivers heartache or that primordial fear of pastors: bad theology?

Consider this case of a vibrant ELCA congregation with a strong connection to their local Lutheran camp. Confirmation students were required to attend camp, and multiple young people served on summer camp staff. Then one week at camp, a young member of the congregation overheard a staff member mumble, “Stupid b****.” The camper was the pastor’s child. The relationship quickly deteriorated, as the director decided not to fire the summer staff member. Challenges at the camp that once seemed minor now seemed like more reasons to withdraw support. Camper numbers from the congregation plummeted. Despite the passage of time and changes in leadership, the relationship has never recovered, with clear consequences for both camp and congregation.

Experiences are powerful. Camp lives and dies through stories. One powerful experience, whether positive or negative, can serve as the prism through which a congregational leader views the camp model as a whole. When they reach the stage of camp skepticism, they are inclined to view every experience through this prism. They are the opposite of the camp enthusiasts, who are so convinced of the power of camp that they can easily contextualize negative experiences. Skeptics are on the lookout for bad theology, safety violations, and emotional manipulation. If they come to your camp (which our survey suggests they probably will not do anyway), they will find these things and confirm their skepticism.

Responding to Skeptics

How do we respond to camp skeptics? There are two commonly used methods that I think are generally counter-productive. The first of these is the fantasy that getting the skeptics to camp so that they can witness its power first-hand will transform them into camp enthusiasts. This is folly. Remember that some of these skeptics are looking for reasons to dislike your camp. They are ready to roll their eyes at every earnest camp counselor who is on fire for Jesus and consider every bug bite a personal insult.

The second fantasy is that surrounding them with camp enthusiasts will change their mind. If you’ve ever sat back and watched camp enthusiasts interact, you know this is a losing bet. If you’re not in on the joke or familiar with the experience, camp people are insufferable.

For camp accommodators, either of these two solutions might reasonably work, since they generally acknowledge that camp is valuable or are, at least, willing to be convinced. We need to move skeptics into the accommodator category before they are willing to consider the power of camp without the impulse to critique everything.

Convincing the Skeptics

My proposed solution is simple: cold, hard facts. Skeptics may never like camp, but they cannot deny that camp gets results. Education is how we move congregational leaders from skeptics to accommodators. This is one of the main projects and strategies of Sacred Playground’s ministry. We have dozens of resources and peer-reviewed research that confirms the transformative power of camp. Importantly, the research also shows that some people have negative camp experiences. It is crucial to acknowledge this fact among the skeptics. It affirms their reason for skepticism, while showing the much larger narrative of positive experiences leading to lasting changes for individuals, families, and congregations.

When you speak to mixed groups of pastors, remember that all three groups are present: enthusiasts, accommodators, and skeptics. Tell your powerful stories of life-changing experiences, but always contextualize these with reliable data. In this way, you will both speak to the hearts of the enthusiasts and appeal to the reason of the skeptics. Don’t expect everyone to love camp because that is simply not going to happen. Instead, work to convince them that camp is a valuable ministry of the church, whether they love it or not.

This post is part of a 4-part series on rostered minister engagement with camping ministries. The findings are based on a December 2020 survey of more than 3,000 ELCA rostered ministers. Other posts can be viewed here: Do Pastors Value Camp?, Ministers who Value Camp, Group 1: Enthusiasts, and Ministers who Tolerate Camp, Group 2: Accommodators.

I wonder what other church structures the skeptics are skeptical of. In other words is this a camp issue or a personality type? I suspect the latter. The church attracts a certain personality type that is narrow and inflexible. Camp is neither.